GUIDED TOUR

One of the most common questions that composers get is “what kind of music do you write?” Interestingly enough, this is one of the most difficult questions to answer. Some try to describe their style as on an imaginary continuum from “noise-based” music to “tonal” music, but these category names are vague and usually place a composer in too narrow a compartment.

In this guided tour, I hope to answer the question about what kind of music I write, how my style has changed thus far, and where I am interested in taking it next. I’m just beginning my career as a composer, so my style will likely evolve dramatically over the coming decades, but I will try to elucidate the ideas that have been important to my composition process thus far.

Association

If I had to pinpoint one thing that acts as a continuous thread throughout my compositions, it is the role that extramusical association plays. I have always made connections between sounds, music, objects, abstract ideas, colors, textures, etc. In daily life, when I perceive a thing (music, an artwork, a person’s face, the room I’m sitting in, anything), my brain spontaneously makes connections to other memories without me even having to actively think about it. Once in a while this happens so powerfully that something in my visual field might trigger a memory of some other (often mundane) experience that took place when I was a child that I didn’t even realize my mind had stored.

This kind of spontaneous association often happens across senses. For example, for me, every letter and word has certain colors attached to it, and the sound of the same word being spoken may have the same or different colors attached to it (many of these colors are pretty strange and disappear if I try to picture them). As I’m listening to music, my mind often spontaneously conjures shapes, colors, scenes, situations, etc.

Much of the time, my senses are so overloaded or used to a routine that they become numb and don’t make strong associative connections. But sometimes, the connection between two things “works” so well that it produces a third “ghost” item or thing – a fleeting, elusive, but extremely powerful idea that would be impossible to think of on its own. These kinds of associations are a rare but wonderful experience in which I seem to see the tiniest glimpse of the mysteries of existence that lie underneath the surface of ordinary life.

Composition Process

When I compose, my goal is to use my own associations to try to reach these complex, powerful "ghost" ideas that lie beneath the surface, by presenting a collection of more tangible ideas and hoping that the listener's mind will spontaneously make a connection between them to create meaning.

My first step usually involves a non-musical idea, and imaginary visual ideas are almost always the primary source of inspiration. Within the past few years, I have progressed from using rather concrete imagined visuals as inspiration to gravitating toward visual ideas that are much more elusive and abstract.

Examples

teratoma, odradek (2014)

flute and pianoTeratoma, Odradek was commissioned by Geoffrey Wilson and written from July-November 2014. This piece began as a collection of abstract visual ideas before I had come up with the title. These ideas weren't concrete, but shared similarities with other more concrete things in my mind, such as

wood

bone

creaking

rough

vicious

in

san

ity

dark

elegant

haunted

skin

rust

organs

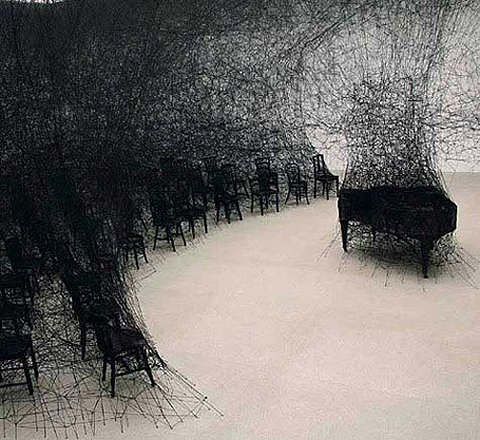

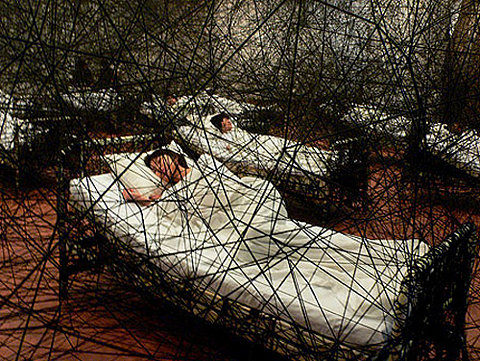

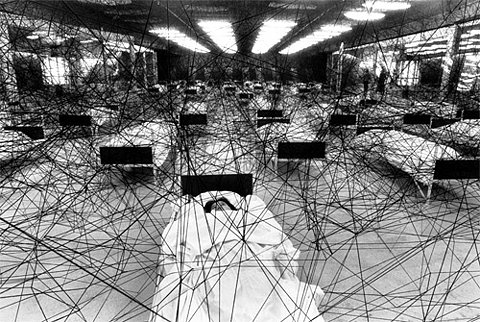

These ideas began to take shape, and I pondered a title. The visceral, bodily images led me to the first thing of the title - teratoma. This, however, didn't seem like quite enough to capture all the ideas in mind. But then I realized the ideas reminded me of something... something I had read a couple of years before in Lawrence Kramer's Interpreting Music - an anecdote used in one of his chapters about a mysterious creature from one of Kafka's short stories. A strange, sentient spool of thread named Odradek who lurked in the shadows of a house. He comes from the strangest little story "Die Sorge des Hausvaters" ("The Cares of a Family Man"), only one page long and delightfully enigmatic.

Odradek solidified some more image associations into the mix - images that naturally complemented and enhanced the original ones:

matted

string

rasping

thread

old

pointless

ness

hissing

wooden

creature

hidden

alive

hair

rattling

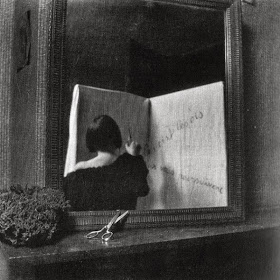

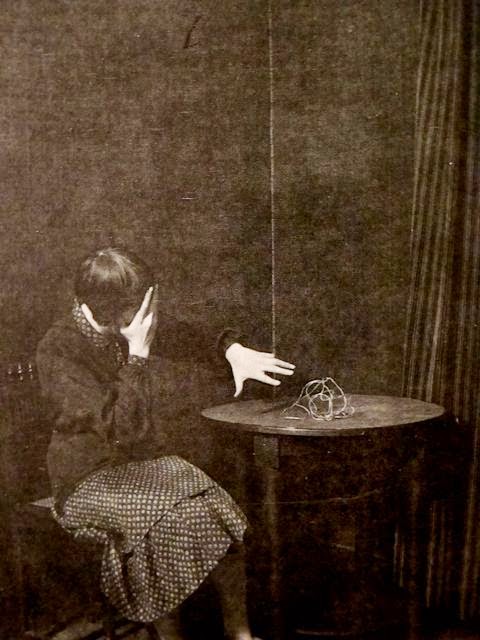

These two things together, teratoma and Odradek, seemed to capture the complete picture I was aiming for. Once I have the beginnings of an idea for a piece, I tend to gather images that fit the idea and use the conglomerate as inspiration. Pinterest is a great tool for quickly gathering a bunch of images into one place so you can see them form one complete picture. I've started using Pinterest as an inspiration tool for many of my recent works (you can follow me here; my composition boards all begin with "Inspiration" and a number).

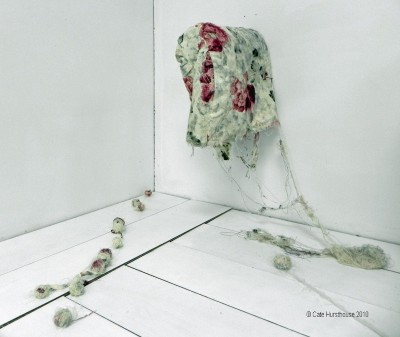

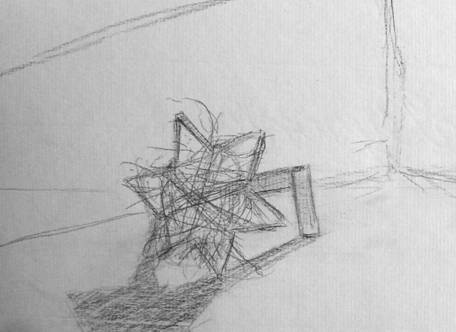

Odradek is a strange character with no cares or purpose. He disappears and reappears as he pleases, rolling around the shadows of the house, speaking nonchalantly when addressed. He's not even a proper spool of thread, but a weird, star-shaped object with a rod protruding out one side, covered in twisted, matted fragments of old string. The "family man" in question describes Odradek uneasily, worrying that this meaningless creature will outlive him. A teratoma, being a tumor, is far more out-of-place and unwelcome, but likewise having no purpose. Furthermore, a teratoma is not even a "proper" tumor, not that there is such a thing, in that it grows cells from elsewhere in the body, even hair and teeth, inside itself.

Once my head is full of images and ideas, the hardest part of course is making music out of them. I already had my instrumentation per the commission - flute and piano - so I began to think of ways in which gestures from these two instruments could conjure the ideas. In high school and college I had played my fair share of French Conservatoire-style flute and piano sonatinas, and so I decided to allude to and mock the genre in my piece. These three-movement works are usually designed to spotlight the flute in a show of romantic and technical prowess. However, in my piece, every time the piano bombastically sets up the flute to enter with a bang, the flute can't be bothered and is caught metaphorically rolling around lackadaisically in a puddle of its own drool. The piece alternates between vicious, snarling, animalistic outbursts and listless, lobotomized reactions. At times it alludes to familiar romantic or baroque gestures, but these have been so distorted and disassociated that they merely add to the uncanny creepiness. The closest the piece gets to a "normal" flute and piano sonatina is the final lively section, mirroring the final movement of a traditional French showpiece. However, even here, the theme is merely the result of the flute holding a non-existent fingering and then depressing or lifting each finger of the right hand in succession, over and over - another purposelessness repetitive motion.

So, now you've seen an inside look at the makings of this piece. However, in the spirit of Mallarmé, who said it was better to allude than to state outright, listeners who hear this piece in performance are given only the following program note as preparation. There is no indication why two words have been used, and no explicit connection between them stated, but the old dictionary format and phrases I've chosen to include should guide listeners just enough in the right direction:

Click here to read musicologist and pianist Geoffrey Wilson's blog post about Teratoma, Odradek.

It's about time we listened to the piece!

BEYOND MACHINES and human fear,

space which was never our frontier (2014)

c/alto flute, clarinet, bassoon, bari sax

Beyond Machines, written in April/May 2014 for the Cortona Sessions (a few months before Teratoma, Odradek), represents a turning point in my style. I wanted to explore a more texture and timbre-based method of composition but still evoke extra-musical ideas just as strongly, hopefully more strongly, than with the mostly melody-driven pieces I had been writing so far. Beyond Machines contains plenty of recognizable melodies, but they are used more as fragments within larger swaths of texture and shape in the service of poignant evocation.

During this year, my second year of grad school, I had been beginning to listen to a lot of Scelsi, Grisey, Saariaho, Zivkovic, and spectral composers, and finding for the first time a genuine awe and excitement over truly new, innovative music. I saw in them a path for myself. At the same time, my goals of strong, abstract extra-musical evocation were solidifying as I read about existing theories of musical meaning and began to develop my own associative model.

The title of this piece refers to different kinds of human portrayals of outer space and the future compared to space itself. Space is often portrayed as frightening and something to be conquered, and much sci-fi film music draws heavily from military calls and marches. In Beyond Machines I mimic this dated sci-fi film atmosphere at times. At other times, I'm mimicking the sound of imaginary machines themselves with pulsating dissonant chords, often including microtonal alterations. At a couple of points in the piece, the fear evaporates, the light pierces through, and we are left with the beautiful and unknown of space without us.

The opening chord was inspired by the opening chord of Scriabin's Prometheus, the Poem of Fire. Scriabin (1872-1915) was also a synesthete (interestingly enough, many of my favorite composers were, or are!). The opening of this piece always seemed so very strange, and otherworldly in an unsettling but intriguing way. Listen to just the first few seconds:

Beyond Machines was the first time I used Pinterest as an inspiration tool. Here's the board in which I gathered images that captured all three of the angles described above:

Here is the final product, with a video I made from still images by Joachim Olofsson (who says on his page that anyone can use his artwork without needing to ask) and some photos from the Hubble Space Telescope.

Alto/C flute: Kaleb Chesnic Clarinet: Madeleine Cort Bassoon: Cameron Burnes Bari Sax: Stephanie Doctor Composed by Chelsea Komschlies Contact: chelsea@komschlies.com Website: www.komschlies.com The incredible digital paintings used here are all by Joakim Oloffson, who has graciously offered his artwork for free use - check him out!

blue fog city, 1922 (2014)

female vocal trioBlue Fog City, 1922, written in April/May 2014 for the Cortona Sessions, was inspired by a recurring dream I had as a child. In the dream, I was alone in an old-fashioned city filled with winding, narrow, cobblestone streets and old-world buildings packed together. It was nighttime, and everything was misty blue. There were no people in the entire city, but some of the buildings had light on inside. There was always one building, a restaurant, that I was heading towards. I could see it in the distance up the street, but when I got close, I saw that the building was actually tiny like a doll house and I couldn't fit inside.

I wrote the text for this piece in one quick, stream-of-consciousness sitting. I was trying to evoke the same mood and images as the dream without stating anything too directly or concretely, lest the contents of the dream itself be lost on listeners. It ended up being words, fragments, and strange sentences. The music was also written very quickly in an unchecked, stream-of-consciousness way. I let the words play out in my head as I jotted down the contours and gestures, notating it later.

I made my second inspiration Pinterest board for this piece:

Genres

Many of my pieces fit into a few broad categories or genres, with some overlap.

Steampunk

Steampunk is a science fiction subgenre taking place in a fantasized version of Victorian-era England. Some of the main features of steampunk are fantastic steam-powered machines and whimsical mechanical contraptions. The term was coined in the 1980s and since then the trend has exploded in popularity.

I first discovered the term "steampunk" in college when I started making jewelry (see some examples of my creations below). The term was new to me, but the aesthetic was very familiar - I now had a term to characterize the kind of style I was already dressing in. I was drawn to steampunk because of the disparate things it brought together: formal elegance, clunky machines, pearls, delicate lace, rusty cogs, filigree, dirt, grime, haphazard wires, fancy scrollwork, whimsy - you get the picture.

Creating A steampunk genre for classical music

When I first discovered steampunk, before I even began making jewelry pieces, I dove into composing my first steampunk piece, aptly titled Steam. The genre already had an established vocabulary of visuals such as those that I've described above, but how might music be steampunk? Well, I mentioned earlier that I associate very strongly across senses and between various senses and memories. A lot of what I do when I compose is to take abstract ideas that are not themselves musical and translate them into music in a way that keeps the original thing as intact and poignant as possible.

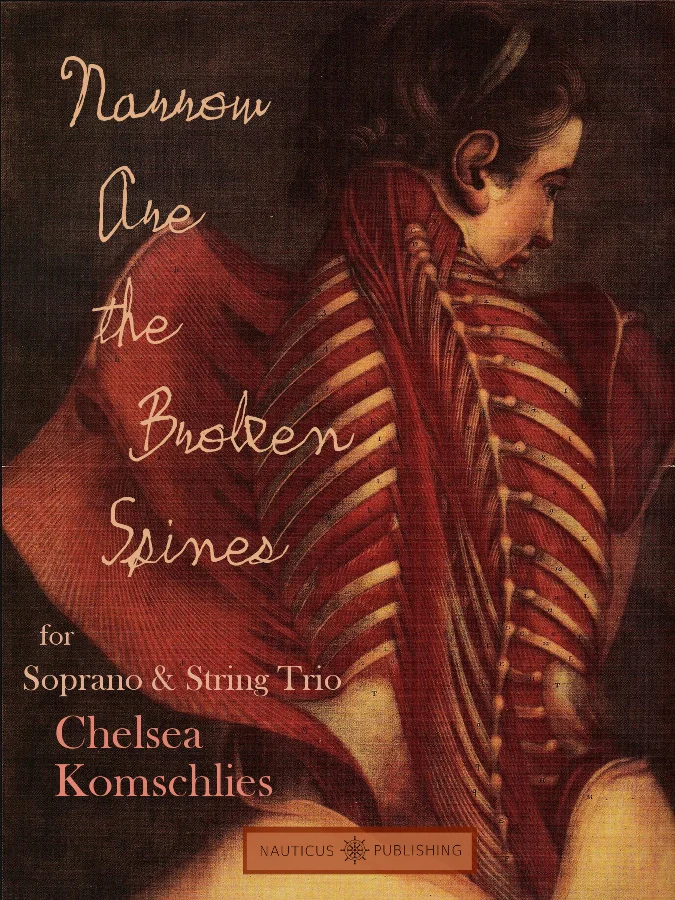

Steampunk often takes something familiar, elegant, or normal and distorts it in a uncanny or whimsical ways. My steampunk music tends to take elegant or familiar elements and distort them in similar ways. Also important is texture. This varies from piece to piece, but choosing instrumental timbres that fit the visual/extra-musical ideas is important. For example, Steam is about an inventor making a flying machine. I used flute and clarinet for their pure, machinelike timbre with certain breathy extended techniques in the flute that evoke puffs of escaping steam. In Narrow Are the Broken Spines, on the other hand, I wanted very raspy, dry, brittle textures to go along with images of old musty books, skeletons, and dolls. I used three string instruments to accompany the soprano, and much of the time their tone is distorted to fit these images while maintaining an elegance and an antiquatedness underneath.